By Peter Callstrom, CEO and Brooke Valle, Chief Strategy and Innovation Officer

In this unprecedented time, the national workforce development system needs $15 billion to deliver the array of services, consistent with investments proposed in the ‘Relaunching America’s Workforce Act’.

Until March 2020 and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, unemployment in the U.S. was at the lowest it had been in 50 years. We had arguably the strongest economy in the world—more Americans had jobs than ever before, consumer prices remained low and the stock market was on the longest economic expansion in history. Then COVID-19 shook our country’s economy to the core.

Prior to this historic event and even more now, the workforce system is woefully underfunded to meet this unprecedented demand. Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) state grant funding for dislocated workers has declined by 40 percent in the last two decades[1]. From July 2018 to June 2019, just over 640,000 adults, 413,000 dislocated workers and 154,000 youth were served by the WIOA system[2]. But during a normal month, almost two million people are laid off or discharged from their jobs.[3] Only about half that many file for unemployment insurance, about 225,000 workers a week, and only about 40 percent of all workers are eligible for unemployment benefits. Far fewer—less than 100,000— receive training through our public workforce system to help them find new, good jobs.[4]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, these numbers reached historic levels. In the six weeks between mid-March and the end of April 2020, nearly 30 million workers filed new claims for unemployment. The U.S. unemployment rate surged from 3.5% in February, where it had remained for some six months, to 14.7% in April and remained above 10% in July even as CARES act funding came to an end[5]. In this unprecedented time, the national workforce development system needs $15 billion to deliver the array of services, consistent with investments proposed in the ‘Relaunching America’s Workforce Act’. This national investment will ensure that we can respond quickly and comprehensively to the current and projected demands for our American workforce to help those who have lost their jobs because of this extraordinary crisis.

Every dollar invested in workforce programs results in positive outcomes: skilled workers, sustainable careers and employed taxpayers rather unemployed tax recipients. The ROI is also very personal: happy individuals and families, self-esteem, perceived value in our society. In San Diego, on average, for every $1 spent on our operations and programs, $2 goes back into our economy as wages and consumer spending[6].

Proper funding levels will enable programs authorized under WIOA—serving adults, dislocated workers and opportunity youth—as well as Wagner-Peyser, Adult Education and Family Literacy, and the Perkins Career and Technical Education Act to meet the unprecedented need.

Specific needs include flexible funding for:

Occupational Skill Building

As the economy recovers slowly, many displaced workers will need new jobs. For our workforce to acquire in-demand careers, they need new and demonstrable skills. Education and training providers will play a critical role in facilitating these transitions. This includes a variety of modalities from on-the-job, to transition jobs to digital learning. This also includes making the wraparound supports, whether access to childcare, PPE or stipends, available so individuals are able to engage with the learning safely and successfully.

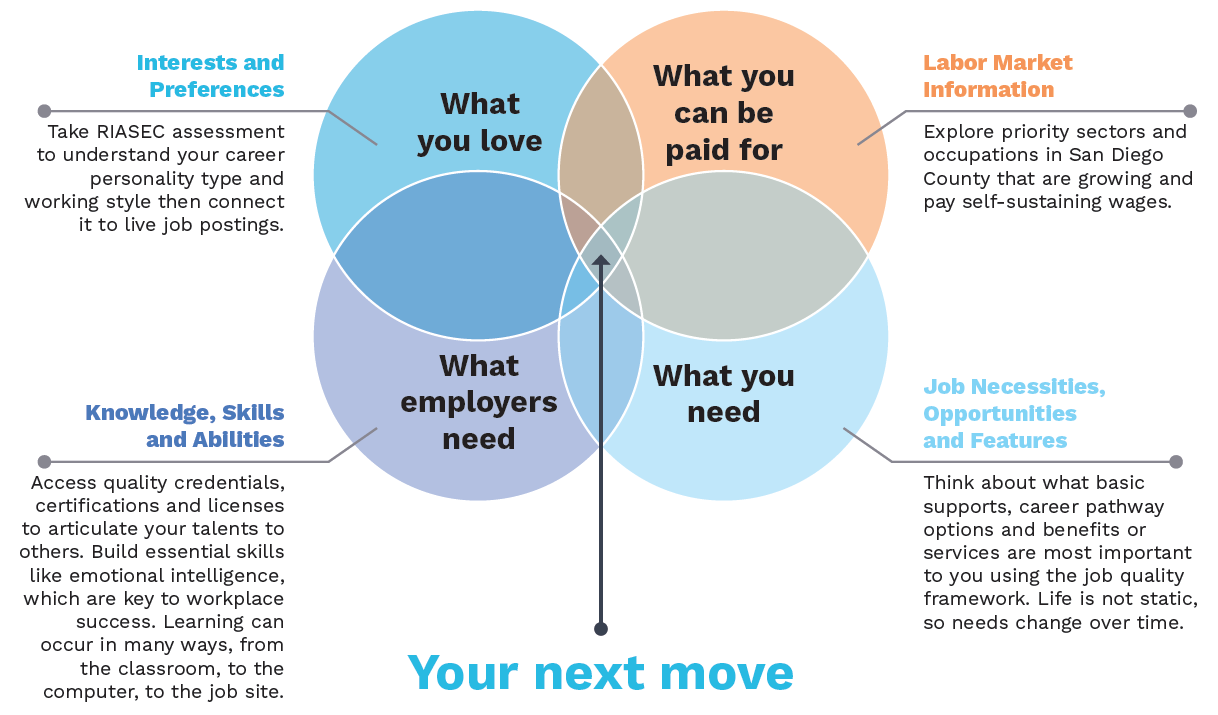

Policymakers are encouraged to support expanding access to skills training by making workers who lose their jobs eligible for a ‘Dislocation Reskilling Account’ as detailed in National Skills Coalition’s report, “A 21st Century Reemployment Accord”[7] providing up to $15,000 in public funds to invest in training through an apprenticeship or other training program, with a community organization or at a community or technical college, to prepare workers who lose their jobs for new jobs created as a result of massive technological shifts in the workplace. Individuals who access the training accounts should receive support to determine their interests and preferences as well as counseling on in demand occupations from the workforce system to invest wisely.

Digital Skill Building[8]

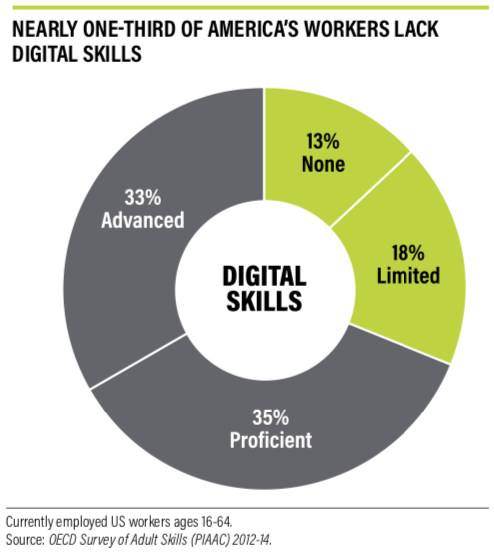

Social services, education and work have shifted online and yet nearly one-third of America’s workers lack the digital skills needed for success. Strategies to support these skills provide personalized support through digital navigators, incorporate employer input in their design, consider “fragmented knowledge”—comfort with one type of technology but not others—and leverage contextualized learning models to rapidly equip workers for the real-life implications of necessary and marketable digital skills.

Social services, education and work have shifted online and yet nearly one-third of America’s workers lack the digital skills needed for success. Strategies to support these skills provide personalized support through digital navigators, incorporate employer input in their design, consider “fragmented knowledge”—comfort with one type of technology but not others—and leverage contextualized learning models to rapidly equip workers for the real-life implications of necessary and marketable digital skills.

- Policy that invests in Digital Literacy Upskilling grants to expand access to high-quality digital skills instruction that meets industry and worker needs is crucial, as laid out in NSC’s “Digital Skills for an Equitable Recovery” report[9]. These dedicated investments are necessary to ensure sufficient attention is paid to digital skill building in the face of numerous competing priorities. Grants should support states in developing and implementing programs that embed digital literacy skills as part of broader occupational skills training, integrated education and training, and other accelerated learning strategies.

- Policymakers are also encouraged to incentivizing private investment in digital skills training, instruction and upskilling opportunities for incumbent workers by expanding the scope of existing tax policies like the Work Opportunity Tax Credit (WOTC) to allow employers to provide essential upskilling opportunities, both in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and over the longer term.

Business Support

Most communities across the U.S. are composed of small businesses in a time where the nation’s small businesses, most of which relied on foot traffic to generate revenue, are facing unprecedented challenges[10]. It is critical to expand Rapid Response (i.e., supports for dislocated workers) and layoff aversion funding (i.e., targeted strategies to help businesses retain rather than displace) to assist businesses in pivoting their models and upskilling workers so that they can be retained through training on new domain knowledge, digital skills and even culture and change management.

Most communities across the U.S. are composed of small businesses in a time where the nation’s small businesses, most of which relied on foot traffic to generate revenue, are facing unprecedented challenges[10]. It is critical to expand Rapid Response (i.e., supports for dislocated workers) and layoff aversion funding (i.e., targeted strategies to help businesses retain rather than displace) to assist businesses in pivoting their models and upskilling workers so that they can be retained through training on new domain knowledge, digital skills and even culture and change management.

Policy must enable local areas to apply innovation in localized, responsive ways to help businesses build quality jobs, which include living wages, pathways for growth and essential supports such as health care. This includes providing increased flexibility to local workforce boards to leverage funds as matched grants, loans or other reimbursement models to encourage businesses to explore commitments to self-sufficiency wages, pooled benefits and staff development.

Changing Infrastructure and Service Delivery Support Needs

Workforce development boards have made a quick pivot in this crisis. However, as we seek to serve this historic demand and shift in our economy, we will need to significantly strengthen our:

- Technology infrastructure investments including the tools necessary to provide services and content remotely as well as upskilling for workforce staff to develop content in this new format.

- Protective gear and retrofitting for our nation’s 2500+ job center locations to ensure we are protecting staff and clients as we deliver modified in-person service. This may include installing protective shields, reconfiguring spaces and expanding cleaning protocols, all of which will incur time and new resource costs.

- Digital access support for our clients—the millions of displaced workers. This includes computers, internet and skilled staff, such as digital navigators, to help unemployed individuals who do not have the equipment, skills needed or knowledge of where to access social services, receive training, perform interviews or participate in work in this new environment.

New American Economy’s research shows that low-income households disproportionately lack access to broadband internet, putting their children at risk of falling behind. More than one in five low-income households did not have any access to the internet in 2018, more than four times the rate of all other households. A staggering 43.7 percent of low-income households lacked access to personal high-speed internet at home, more than double that of the rest of the population[11].

Addressing Gaps in Racial Equity

While the need to address racial inequities is not new, policymakers have a unique opportunity to make a positive shift by acknowledging that with a system and society with unconscious bias and built-in barriers, people of color often experience barriers from birth to enter the labor market and must work significantly harder to obtain similar opportunities for success. The Bureau of Labor Statistics confirmed that the country ended the month of May with unemployment rates in the Black/African-American and Hispanic/Latino communities that were markedly higher than for white individuals.

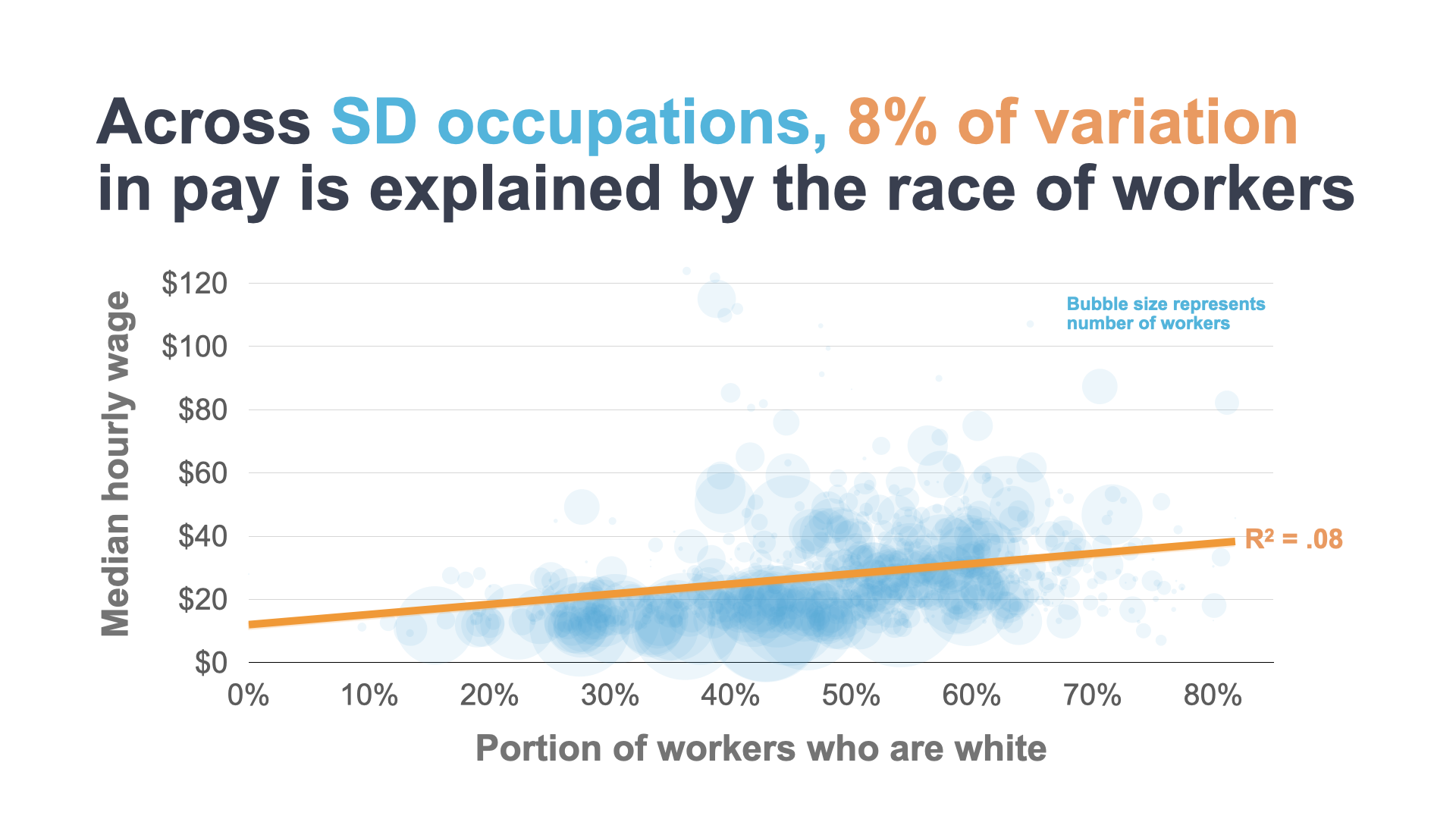

Structural racism has led to an over-representation of workers of color in low-wage jobs[12]. The lack of access to training is putting families at risk and widening the race and gender divide. Indeed, a recent Brookings report[13] showed that 49% of San Diegan’s make less than $18 dollars per hour, less than one dollar above the Self Sufficiency Standard[14] for San Diego. In a study of front-line jobs in retails sector jobs, we found that nonwhite workers are more likely to be placed in low-wage occupations giving them far less access to the resources needed to advance. If we consider only the top retail occupations, the racial composition of occupations accounts for 51% of the variation in average occupational wages.

Policymakers must:

- change the workforce narrative about and for people of color (and those with disabilities, and all marginalized groups)

- challenge those individuals and systems who choose to devalue people as uneducated or unmotivated and

- encourage local use of federal and state funds to proactively address gaps that have been created systemically (e.g. prioritizing funds for black youth in communities where black youth disconnection is disproportionately high relative to other racial groups).

Policymaker support is also necessary to eliminate barriers around data and success measurement.

Data Sharing

Legislation that encourages access to/breaks down barriers around access to data is crucial for local areas to serve the whole person. Individuals in crisis are often leveraging the services of a variety of different systems from workforce, to children’s services, to education or the justice system. Currently, critical data sits in disparate locations, often requiring those we serve to tell their story multiple times, delaying access to critical supports and even creating benefits cliffs. Overcoming this unacceptable inefficiency is at the center of more effectively serving job seekers.

The more that legislation at the federal level can encourage data sharing the easier it becomes for state agencies to establish MOUs to serve their communities. This imperative goes hand in hand with maximizing eligibility for and access to additional support services under existing federal programs for workers during the reemployment process.

Barriers to accessing child care[15], transportation and other support services—such as eligibility that doesn’t permit workers to access subsidies while in training programs or underfunding that leads to long waiting lists—make it harder for workers to succeed in training programs necessary for reemployment. Fifty-seven billion in lost earnings, productivity and revenue are lost nationally due to the child care crisis alone. Closures of schools and childcare facilities during this pandemic, will only drive this number higher forcing parent to choose between caring for their children or earning an income, a choice no one should be forced to make.

Impact-Focused Measurement Approaches

Currently WIOA requires the measurement of outputs—delivering training and serving clients—and a limited number of outcomes—number of clients who found work—but provides little incentive for innovation and impact. Policymakers can support the work on the ground through the implementation of performance measures in both WIOA and other stimulus packages that shift measurement focus to impacts. This would encourage local areas to establish innovative partnerships to achieve the desired goals, structure contracts using performance-based measurements, and build their data collection, analysis and decision-making around how our services really change the lives of our clients and their communities[16]. Areas of focus might include wealth building, employee ownership, debt reduction, stable housing, reduce recidivism, etc. Policymakers are also encouraged to consider the importance more flexible timelines for meeting performance during the pandemic as well as the ability to identify relevant metrics for measuring success for special populations (e.g. success for the justice involved might look different from a veteran or an opportunity youth).

Contact: PeterC@workforce.org or BrookeValle@workforce.org

References

[1] https://www.nationalskillscoalition.org/national-initiatives/body/CIAW-Invest-in-AW.pdf

[3] https://www.bls.gov/news.release/jolts.nr0.htm

[4] https://www.dol.gov/ui/data.pdf and https://www.doleta.gov/performance/results/Quarterly_Report/2018/Q3/WIOA_Dislocated_Worker3_31_2019Rolling_4_QuartersNQR.pdf

[6] https://sdwp.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=5dcdcea0b9c74b259549251b2cd51fb1

[7] https://www.nationalskillscoalition.org/resources/publications/file/Remployment-Accord-web.pdf

[8] https://nationalskillscoalition.org/resources/publications/file/New-Digital-8Landscape-web.pdf

[11] https://research.newamericaneconomy.org/report/internet-access-covid-19/

[14] http://www.selfsufficiencystandard.org/california

[15] https://childcare.workforce.org/

[16] https://results4america.org/tools/2019-invest-works-federal-standard-excellence/ and https://results4america.org/tools/2019-invest-works-state-standard-excellence/