By Shaina Gross, VP of Client Services; Research by Daniel Enemark, Ph.D., Senior Economist @danielenemark

Tweet this article

U.S. women lost 156,000 jobs last month, while men gained 16,000.

When I first read this startling statistic from CNN on my social media feed, my hopeful heart said that can’t be true. Which was immediately followed by my knowing head saying of course it is true.

Because, as a woman in the workforce, I know all too well that more often than not we are the ones whose career paths are sacrificed for our families. We are the ones working harder and getting paid less. We are the ones fighting for equality, not just in wage but in opportunity. And that fight is even more difficult for women of color, whose unemployment rate is nearly two thirds higher than that of white women.

Make no mistake—these inequities have deep, long roots that are being brought to light by our current circumstances. Beyond the wage gap, women have faced discrimination and disadvantage in the workplace for decades.[1]

I recall one position I held where I had worked my way up over a few years. When the promotion was official, I was so proud to have finally achieved a professional goal. A few months later I discovered that my newly hired male colleague was getting paid more than me for the same job. My pride immediately vanished. Happily, I can report that after bringing this to the attention of the hiring manager, adjustments were made. But too many women face a much different ending.

Gender Wage Gap or Mother Wage Gap

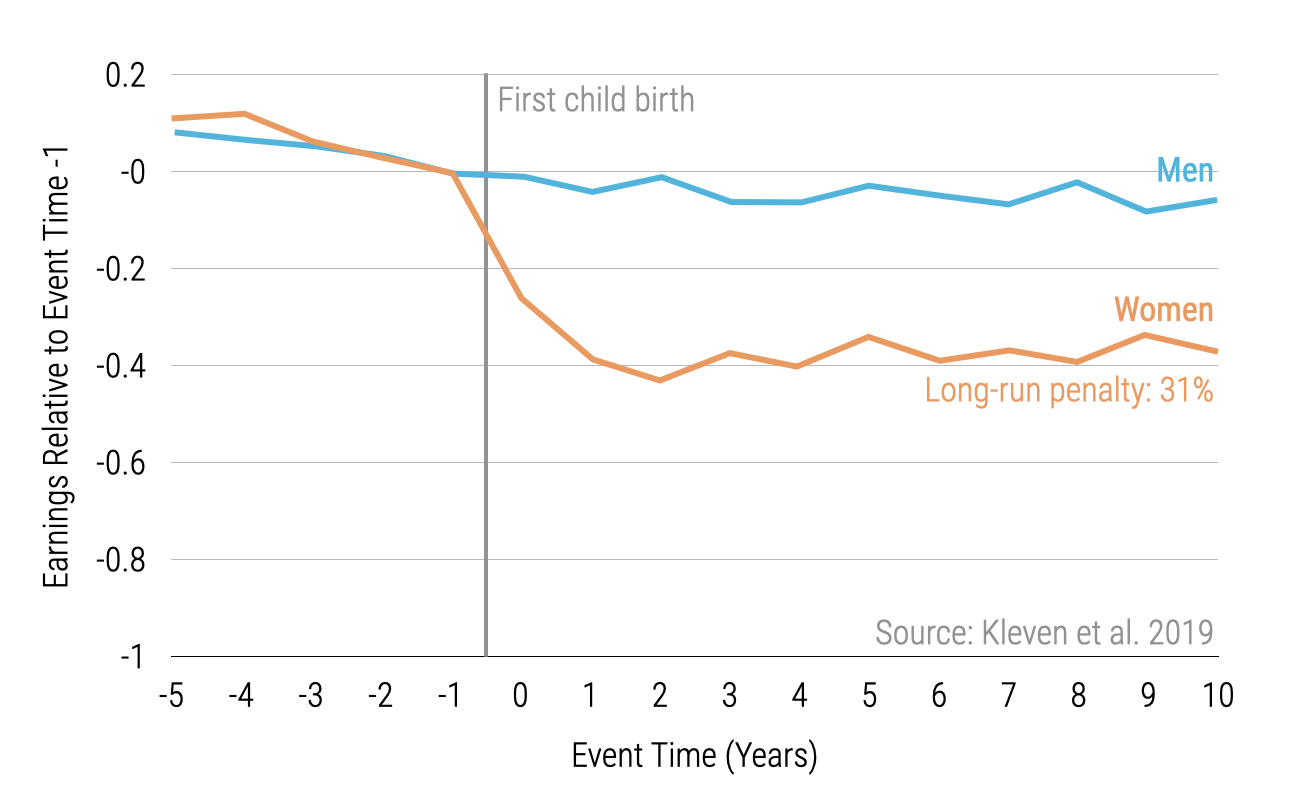

While the overall gender wage gap has narrowed over time, research shows that today the greatest inequality is the so-called “child penalty” for mothers.[2] Moreover, audit studies and experiments show that among women with identical resumes, those with children are rated as less competent, viewed as worthy of lower salaries, and receive fewer callbacks from employers than those without children. By comparison, men with children suffered no such penalties.[3]

As a mother this rings painfully true for me. Mothers face agonizing decisions as they choose between A) being present and home for the first critical months of their child’s life, establishing a rhythm with their newborn, enjoying these precious first moments and recovering physically and mentally from a truly incredible feat, and B) ensuring they keep their job, don’t miss out on promotion opportunities, continue to demonstrate their value to the workforce and prove that having a child hasn’t changed anything about their ability to do their job.

I have always worked in the nonprofit field and most of my colleagues have been women. When I had my son four and a half years ago, I felt well supported at work. And yet, within three weeks of being on maternity leave, I began to wonder what I was missing, what was happening without me, if I was being left behind, and if my position was still valued.

I began to feel a self-imposed need to remain relevant, involved and present in the workplace. I wonder how much of this was my own type-A personality, and how much of this was an informed reaction to all the things I had witnessed and experienced throughout my career.

A year later when I had an opportunity to level-up to a CEO position at a new organization, I knew my success depended on the support I could receive from my partner and family. I was only able to pursue this opportunity while having a one-year-old at home because my husband transitioned to part-time work and my parents who lived nearby shared in the child care responsibilities. I am well aware of how privileged I am to have these options and large support network. And yet, I still felt daily internal conflicts about balancing my evening work commitments with missing bath and bed time. I couldn’t help but wonder if any of my male counterparts were having the same struggle.

It’s often said that when men put a picture of their family on their desks, people think they are compassionate, accomplished and balancing it all; but when women put a picture of their family on their desks, people think they are distracted, weak and unproductive. The mental energy that women have to spend on navigating the workforce and their careers is immeasurable. How to be assertive but not off-putting; how to make sure my ideas are heard and not discarded; how to lean confidently into my experience, education and training and quiet the imposter syndrome rhetoric echoing in my head.

COVID-19 and the Exacerbated Child Care Crisis

“Other countries have social safety nets. The U.S. has women.”

–Jessica Calarco, Sociologist

The 156,000 jobs women lost last month comes primarily from three, traditionally female-dominated sectors—education, hospitality and retail. Many of these jobs are low paying jobs and typically lack sick leave and the ability to work from home.

As COVID-19 has uniquely highlighted, when work and family come into conflict, women leave the workforce.

Census data reveals the average price of child care for two young children in the San Diego region consumes 40% of the budget for a typical family of four. So you can see how too often the math just doesn’t pencil out to keep working. As sociologist Jessica Calarco said, “Other countries have social safety nets. The U.S. has women.”

How to Fight Gender Inequality in the Workplace

Make Child Care More Accessible

Ninety-four percent of U.S. workers involuntarily working part-time due to child care needs are women.[4] This is an especially big challenge in San Diego, which has the second lowest female participation in the labor force among major American cities. Quality, affordable, accessible child care would alleviate gender inequality.

Before the pandemic, San Diego had 335,000 children under 12 with no stay-at-home parent, but only 145,000 available child care spots, leaving us with a shortage of 190,000. School closures have only exacerbated this problem. The steps that both the City and County of San Diego have taken to support accessing child care during this pandemic are a good start. But we still have further to go.

Champion Job Quality

Let’s begin by recognizing that workers who have been deemed “essential”— the check-out clerk at your local grocery store or Target, your child’s teacher, the home health aid taking care of your aging parent— are not paid as if they are essential. We must do more than say “thank you” and cheer for them each night.

At the San Diego Workforce Partnership, we advocate for jobs to pay a “self-sufficient wage.” Currently, that is a minimum of $17.65 an hour. Beyond wage, job quality includes access to benefits, having a predictable schedule that allows you to coordinate your other responsibilities—such as after-school pick-up or a partner’s schedule—and having opportunities for advancement. Many of our programs prioritize women, and BIPOC communities so that we can begin to close the opportunity and wage gap.

Create Flexible Workplaces

If the pandemic has done nothing else, it has proven that flexible hours and virtual/remote work can be extremely effective and productive for the segment of workers whose jobs went remote. More than that, it provides an opportunity for employers to acknowledge the human realities that many workers, including themselves, face. It places trust in a worker to juggle their responsibilities (something they have been doing behind closed doors previously), while still getting the job done.

I will admit, I struggled with this at first. I worried if my team would be as productive. I wondered about people being able to work, while also home schooling. I questioned the impact on our team’s ability to work collaboratively as people were piecing together new schedules with hours that crept into the evening after kids were asleep. But, it has worked—for the company and its goals and the employees feeling seen and valued. And we continue to work on it together, finding unique solutions to unique circumstances. As a woman and mother, I was committed to doing this for my coworkers.

What we need is a culture shift. We need to no longer value productivity above sanity or, advancement above family. We need taking maternity and paternity leave, or advocating for extended parental leave to never be seen as a vacation or a choice to take your foot off the gas pedal of your career. We need people, policies and plans to systemically reduce inequality and reverse time-old tradition and toxic stereotypes.[5] Without that, we will never get to a place where women are equal.

[1] For just a few examples, see these studies: Heilman, M. E., & Haynes, M. C. (2005). No credit where credit is due: attributional rationalization of women’s success in male-female teams. Journal of applied Psychology, 90(5), 905. Hoobler, J. M., Wayne, S. J., & Lemmon, G. (2009). Bosses’ perceptions of family-work conflict and women’s promotability: Glass ceiling effects. Academy of management journal, 52(5), 939-957. Roth, P. L., Purvis, K. L., & Bobko, P. (2012). A meta-analysis of gender group differences for measures of job performance in field studies. Journal of Management, 38(2), 719-739. Parker, K. & Funk, C. (2017). Gender discrimination comes in many forms for today’s working women. Pew Research Center.

[2] Kleven, H., Landais, C., Posch, J., Steinhauer, A., & Zweimüller, J. (2019, May). Child penalties across countries: Evidence and explanations. In AEA Papers and Proceedings(Vol. 109, pp. 122-26).

[3] Correll, S. J., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112(5), 1297-1338.

[4] Committee for Economic Development (2019) Child Care in State Economies.

[5] Research shows, for example, that women’s contributions to teams are undervalued.

Heilman, M. E., & Haynes, M. C. (2005). No credit where credit is due: attributional rationalization of women’s success in male-female teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 905.