As part of our continuous learning and improvement of our programs and projects, the San Diego Workforce Partnership held a Reentry Works Town Hall to hear from community stakeholders how best to create a request for proposals for approximately $2M in funding to serve current and formerly incarcerated individuals throughout San Diego County reentering the community. Approximately 75 attendees engaged in a community conversation on creative solutions to solicit high-quality applications.

As the unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people is nearly five times higher than the unemployment rate for the general United States population and substantially higher than even the worst years of the Great Depression, we convened community-based organizations, nonprofits, businesses, criminal justice partners, earn-and-learn providers, volunteers and justice-involved individuals to address the crisis of finding employment after incarceration.

Patricia Ceballos, Reentry Services Assistant Manager with the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department, said “We don’t want jail to be the resource.”

The question is, how do we offer relevant resources to individuals being released from prison returning to our communities?

The Workforce Partnership’s VP of Operations Andrew Picard, Sr. Research Specialist Daniel Enemark and Manager of Programs Kristen Walker shared more about what we are currently doing around reentry services.

Enemark shared that the recidivism rates between San Diego and Imperial counties are two ends of a spectrum. While San Diego County has the lowest rate of recidivism* (36 percent) of any large county in California, Imperial County’s is 71 percent, the highest in the state. Understanding this discrepancy will help us serve our region better.

Walker shared that the guiding principles in our previous RFP were informed by conversations with people. We had learned that:

- Change is driven by trusting relationships. This includes partnerships across supporting organizations and justice-involved individuals and supporting organizations.

- If organizations seek to support justice-involved individuals, the best time to reach them is before they are released from custody.

- A job isn’t always the first step toward self-sufficiency: If justice-involved individuals believe all an organization cares about is achieving employment placements, they won’t communicate challenges that are relevant to their path toward self-sufficiency.

- Organizations that want to support this population need to agree on a model of service that provides justice-involved individuals experience over the operational preferences of their organizations.

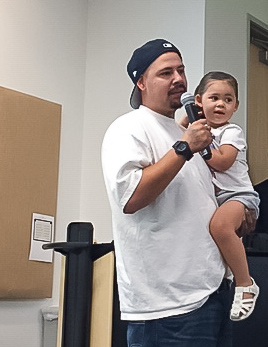

Attendees then heard from three individuals with lived experience with incarceration—prison reform advocate Jay Jordan, who shared on YouTube his personal challenges and work with the #TimeDone campaign; Eric Rosales, a single father who shared his personal journey of finding work as a bus driver for the City of San Diego; and local advocate Alberto “Beto” Vasquez, a biology teacher who spoke about community needs from his perspective.

Rosales’ emotional testimony summed up the need for funding for post-release support services. When he connected with his local career center’s New Beginnings program, he qualified for $5,499 in training dollars, which he put toward truck driving courses.

Rosales’ emotional testimony summed up the need for funding for post-release support services. When he connected with his local career center’s New Beginnings program, he qualified for $5,499 in training dollars, which he put toward truck driving courses.

Rosales remembers feeling accepted. “No one judged my tattoos.”

Though he did not acquire a Class C truck driving license, Rosales obtained a Class B Commercial Driver’s License—a requirement for heavy and tractor-trailer truck drivers and bus drivers.

And while Rosales cautions that not everyone in jail wants help, “there are some good solid people in there who just don’t know the way. This funding helps people.”

Vasquez added, “We all want to feel like we belong in something—the feeling of ‘somebody gave a damn’.”

To that end, “Not only do people need mentors,” Vasquez said. “We need to teach people how to be mentors themselves.”

Vasquez recommends other commitments we can make:

- Increase interest in STEM among minority students

- Increase educational opportunities for currently and formerly incarcerated populations

- Provide professional development for staff

- Help student-led groups

- Become an advocate

In addition, Vasquez asked us to consider the following when designing projects and programs:

- What programs/organizations currently exist? What needs do they address?

- How can we purposefully collaborate with small organizations? (They work more closely with people)

- Do you include individuals with lived experience?

- Are we valuing their time?

Attendees had the chance to offer input after hearing from the speakers. The collective focus was on working together and unifying our individual program efforts in supporting men and women who have been incarcerated.

From the discussion, we heard:

- We must consider holistic needs of a person as we are serving multifaceted human beings.

- There are no one-size-fits-all solutions.

- Access to equitable employment and educational opportunities support quality of life.

- Large organizations need to work with smaller grassroots organizations within the community to meet the unique needs of our justice-involved community members; not one organization or agency can do all the work.

- Everyone must be invested in our justice community.

- Each representative has what is necessary to build positive relationships to support the success of our returning citizens with the necessary resources such as housing, mental health, family reunification and employment.

- Support from the community will drastically lower recidivism and increase positive long-term outcomes.

- Establishing trusted relationships is the key.

Reentry Works 2.0

In the same spirit of listening and learning, we used lessons from our first Reentry Works special project to design the latest program. Those lessons include:

- It is important to provide uninterrupted supportive services (maintain continuity of pre-release service to post-release service).

- We must use an individual-based approach and address criminogenic needs—characteristics, traits, problems, or issues of an individual that directly relate to the person’s likelihood to re-offend and commit another crime.

- Increased post-release supportive services decrease recidivism—as defined by conviction rates.

To see how you can help with our reentry efforts, contact us at reentryRFP@workforce.org.

*The CDCR considers conviction rate the primary measure of recidivism.