Every year, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) choses a theme to help celebrate Black History Month. This year’s theme, Black Resistance, calls us to “study the history of Black Americans’ responses to establish safe spaces, where Black life can be sustained, fortified, and respected.” That history includes labor and worker rights.

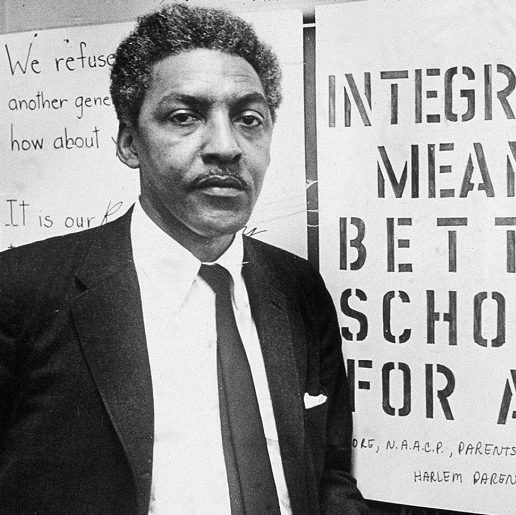

Per ASALH, to resist inequality and to advocate for themselves, Black men and women formed labor unions based on trades and occupations. Black people have also turned worker power into political power to seek their rightful place in this country. The historic Executive Orders 8802—Prohibition of Discrimination in the Defense Industry, and 9346—Establishing a Committee on Fair Employment Practice, were responses to A. Phillip Randolph’s work, including the March on Washington.

Randolph was the leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), the first predominantly Black labor union granted a charter by the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and soon expanded his efforts to other industrial areas. Randolph was also one of the founders of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR), which has served as a major civil rights collation. Randolph worked closely with Dr. Martin Luther King to advance economic and civic equality.

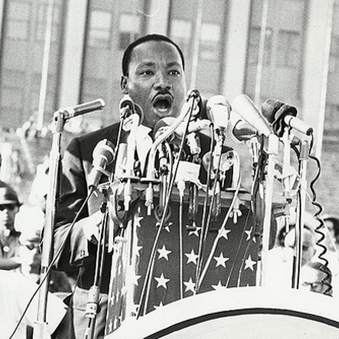

King spent a significant amount of time advocating for the rights of workers. He supported workers on strike, promoted unions and gave many speeches on labor as a tool to support minorities. The March on Washington, best known for his “I Have A Dream” speech, was a March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

On March 18, 1968, King delivered his speech “All Labor Has Dignity” at the Bishop Charles Mason Temple of the Church of God in Christ in Memphis, Tennessee. The attendees were primarily sanitation workers on strike and their supporters. King talked about the societal importance of every job, sanitation included and about how low wages and lack of labor rights kept certain groups oppressed.

“Do you know that most of the poor people in our country are working every day? And they are making wages so low that they cannot begin to function in the mainstream of the economic life of our nation. These are facts which must be seen, and it is criminal to have people working on a full-time basis and a full-time job getting part-time income. You are here tonight to demand that Memphis will do something about the conditions that our brothers face as they work day in and day out for the well-being of the total community. You are here to demand that Memphis will see the poor,” said Dr. King.

Another partner to King and Randolph was Bayard Rustin. Rustin fought for more than four decades to promote civil and labor rights for Black people. Through his work, he was able to influence President Roosevelt’s issuing Executive Order 8802, which created the Fair Employment Practices Committee. In 1965, Rustin and Randolph established the A. Philip Randolph Institute, which continues today to fight for social, political and economic justice for all working Americans.

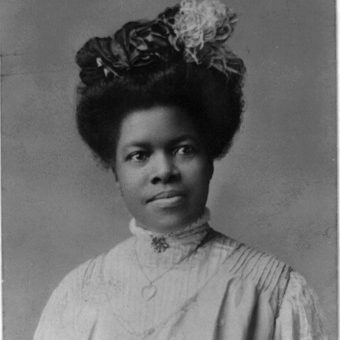

Alongside King, Randolph and Rustin, was Nannie Helen Burroughs. In 1921, Burroughs organized the National Association of Wage Earners (NAWE) to improve conditions for Black women laborers. Burroughs also organized the National Trade School for Women and Girls (NTS), from which hundreds of women graduated and then entered the workforce. She also co-founded the National League of Republican Colored Women (NLRCW) to encourage voters and introduce policy change. Burroughs’ initiatives to document systemic inequalities eventually became of interest to the White House and she was appointed to be the chairman of the Committee on Negro Housing in 1931.

For almost a hundred years, marginalized communities across America have fought for equitable treatment at work. While some progress has been made, overwhelmingly the data shows that BIPOC communities are still far behind white workers in terms of wages and access to some industries.

So why is workforce inequality still so rampant, including in San Diego?

Systematic oppression still runs deep. Hiring and housing discrimination, access to capital and biased policing are just a few of the systematic barriers BIPOC people face every day.

“The history of systemic racism in America—and San Diego in particular—has created a regional economy in which people of color do not have access to the same opportunities as white San Diegans. As a result, even controlling for age, gender and education, Black San Diegans make $10,500 less [annually] than their white peers,” shares Daniel Enemark, Chief Economist at SDRPIC, formerly at the Workforce Partnership.

Inequality at work furthers inequality in areas like housing, education and food security. In America’s world of work, where an individualistic mindset and culture is too often the norm, it’s imperative to shift focus to correcting the systems that uphold this inequality, as we also recognize our own roles within them to make change.